[ad_1]

This is an excerpt from Second Opinion, a weekly analysis of health and medical science news. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

The current staffing crisis in health care has reignited debate over privatization of the Canadian system — and while more needs to be done to take the pressure off hospitals, critics say more private care is not a “simple solution.”

This week, Ontario Health Minister Sylvia Jones revealed a plan to help stabilize the province’s health-care system that included increasing the number of publicly funded surgeries performed at existing private clinics, though she declined to provide details on which specific facilities would be involved or which surgeries would be covered.

“Health care will continue to be provided to the people of Ontario through the use of your OHIP card,” she said at a news conference Thursday, declining to answer a question about whether she would consider allowing more private clinics in the province.

Depending on who you ask, increased privatization is either a growing threat or a possible solution to the staffing crisis being felt across the country.

Yet for-profit clinics for surgeries and other medical practices have existed to varying degrees across Canada for decades, and commercial agencies have been quietly filling staffing shortages during the pandemic — at a growing cost to hospitals and taxpayers.

Proponents argue some privatization would take pressure off the public system and better triage care, while those opposed worry it would siphon off resources and increase inequity among Canadians.

“Right now, we find ourselves in a really challenging situation, because the health-care system is currently not functioning well — and I think that’s becoming more apparent day by day,” said Dr. Katharine Smart, president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA).

“Privatization always is one of the things that people bring up in that conversation,” she said. “But I think what we really need to be considering is how would that actually improve service delivery for Canadians, to suddenly have a private, for-profit model?”

Private clinics aim to fill gaps in care

Canada is facing a critical shortage of family doctors, with millions of Canadians without access to primary care because of retiring physicians and fewer medical school grads choosing the specialty due to a lack of resources and high overhead costs.

The pandemic has also exacerbated a lack of access to emergency care and increased wait times for surgery, with close to 600,000 fewer surgeries performed between March 2020 and December 2021, compared to 2019, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Almost half of adults across Canada’s 10 provinces had difficulty accessing health care in 2020 and 2021, while close to 15 per cent said they didn’t receive the care they needed at all, according to a 2021 survey from Statistics Canada.

WATCH | What’s behind the shortage of family doctors in Canada?

Family physicians Dr. Kamila Premji and Dr. Rita McCracken discuss the shortage of family doctors in Canada and what can be done to ease the situation.

Private clinics have moved in to try to fill that gap in some provinces, including Quebec and Nova Scotia. Others are pushing back against the notion of offering more private health care.

In British Columbia, the province’s highest court recently upheld a lower court’s dismissal of a Vancouver surgeon‘s challenge of the Medicare Protection Act, ruling that bans on extra billing and private insurance do not violate charter rights.

As it stands, Canada’s health-care spending is divided between the public and private sector at roughly a 75-25 split, and at a cost of about $6,666 per Canadian, according to CIHI. Private health-care services are paid for by patients primarily out of pocket, as well as through private insurance.

The country was projected to spend more than $300 billion on health care in 2021, which represents nearly 13 per cent of the GDP. That puts Canada roughly on par with other wealthy countries. (The United States spends the most on health care of any country in the OECD.)

Dr. Adam Hofmann is owner of Algomed, which has private clinics in Quebec and Nova Scotia, where it charges clients a subscription fee of $22 per month out of pocket, plus $20 per visit. Hofmann said while he was once a staunch defender of a publicly funded health-care system, he now believes private clinics are part of the solution.

“A large number of patients that end up in the emergency room are there for conditions that can be treated or prevented in an outpatient primary care clinic,” he told CBC’s The House. “And these patients almost universally don’t have access to primary care.”

These kinds of private options should be explored on a broader scale as Canada seeks to solve its health-care challenges, said Janice MacKinnon, a professor of public policy at the University of Saskatchewan and a former provincial finance minister.

“We have to do everything we can to make the system more effective, more cost effective, and more accessible to people,” she told The House, adding that other countries, particularly in Europe, have developed models where both public and private systems can co-exist.

“No government is saying: We don’t want to fix the public system, we want to create a separate one. They’re saying we need to fix the public system and we see private options as a way to do that.”

Privatization ‘not a simple solution’

Colleen Flood, a research chair in health law and policy and professor at the University of Ottawa, has looked at health-care systems around the world and she says private care tends to make access more difficult for low-income residents.

Flood described privatization as a “zombie solution” that we “pull out all the time, instead of focusing on how to fix the public health-care system.”

“It’s not a simple solution,” she said. “Countries that have public-private systems, they spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to regulate the private [sector] so that it doesn’t absorb all the resources from the public health-care system.”

In general, she explained, private clinics tend to target less complicated procedures — such as knee and hip surgeries — but the public system is still relied upon for emergency services and complex treatments for conditions like cancer and heart disease.

“So you are diverting labour … not only to the relatively small percentage of the population that can pay for that or have private insurance,” she said, “but you’re also diverting them from really important care.”

Ontario’s plan to fund private clinics with public money could potentially be a more efficient way to provide service, depending on the cost, which is ultimately footed by taxpayers, said Maude Laberge, a professor in health economics at Laval University in Quebec City.

“That’s a negotiation aspect between the government and those clinics,” she said. “As long as the patient doesn’t have to pay.… If a clinic can do something really well — as well as it’s done in the hospital or in the public — then there’s no problem with having such private, specialized clinics. If the patient has to pay, then it brings equity issues.”

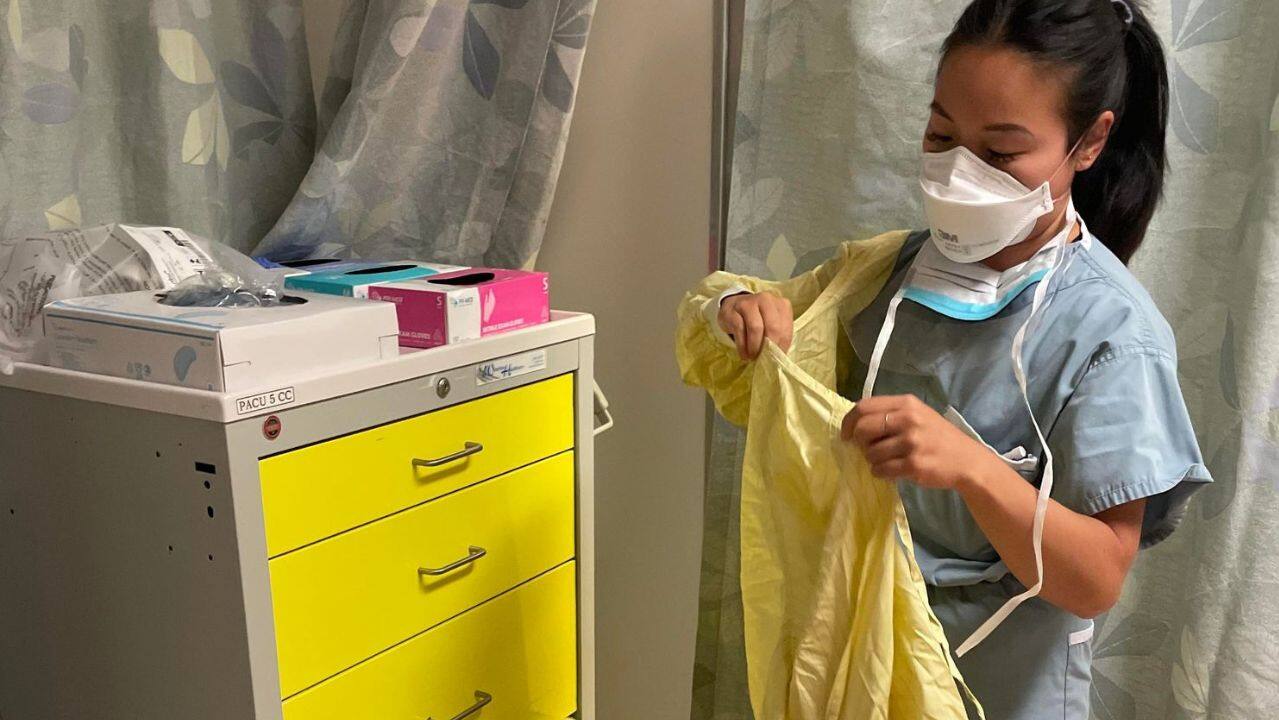

Hiring staff from private temp agencies hasn’t seemed to solve the crisis in Ontario, where some hospitals have paid millions more to such firms to help staff intensive care units and emergency rooms, at an hourly rate more than double that of unionized nurses, as first reported by the Toronto Star this week.

“Where’s the stewardship for our tax dollars?” said Dr. Michael Warner, critical care medical director at Toronto’s Michael Garron Hospital. “And then what is that money not being spent on because it’s being spent on nurses?”

WATCH | Critics sound alarm over Ontario’s reliance on private nursing agencies:

With a shortage of nurses in Ontario, hospitals are increasingly relying on temporary agency nurses to help fill the gap. Critics are raising concerns that public dollars are going to these private agencies, instead of toward better wages for nurses.

Toronto’s University Health Network (UHN) spent just over $1 million to hire nurses from various agencies in 2018 — but that increased to more than $6.7 million in 2022 alone, more than $4 million of which was tied to hiring private nurses to work in its ICUs.

“What we’ve seen during COVID is that these agencies are charging much more, and I’m not sure where their money is coming from, but hospitals are paying much higher hourly rates,” said Warner. “What they’ve done during the pandemic has been predatory and exploitative.”

Transforming the public system?

Those in favour of privatization say the Canadian health-care system desperately needs to be open to new ideas, with Jones, Ontario’s health minister, saying last week that Ontarians should not be afraid of “innovation.”

But critics say there is little evidence to suggest the situation is improving with the private services we already have —despite costing considerably more — or that more of it will help.

“While there may be ways to improve the system, for sure, with innovation … we have to be clear on what exactly that we’re privatizing and how that’s going to cost less and deliver better outcomes,” Warner said.

“It makes more sense to transform the public system than to nibble around the edges with private health care.”

The CMA’s Smart said previous examples of private companies delivering health care in Canada “skim off the easiest, most simplistic” areas and fall short of developing an ongoing, meaningful relationship between the patient and doctor.

“It doesn’t do anything for patients who have chronic and complex needs; it doesn’t do anything for patients who may be having challenges because of social determinants of health,” she said. “Those people are left behind, for an under-resourced public system.”

[ad_2]

Source link