[ad_1]

It’s 6:30 a.m. and a section of the Emergency Department at Kingston General Hospital is closing for the day. The lights are out so patients can sleep, but one by one, they’re woken up and told they are being moved.

“Most likely, quite a few will end up in the hallway by the time we’re finished … It’s not very nice,” said Monica Griffin, a charge nurse at the Ontario hospital that’s a trauma centre for about 500,000 people in the area.

The reason? There is not enough staff to keep Section C — reserved for the least-sick patients — open for the day shift. They’re short two nurses, so patients need to be moved elsewhere in the department.

“It’s like this all the time — or worse,” said Griffin.

Ongoing and widespread staffing shortages in health care mean even a large urban hospital like Kingston is affected. Many doctors and nurses across Canada have been calling for help for months, as the COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed resources that they say were already stretched — leading to an unparalleled wave of staff shortages that they say is reaching a breaking point.

According to Ontario Health, 18 hospitals in the province have had emergency department service interruptions since the end of June, most often for an overnight shift, due to a shortage of nurses.

About 46,000 more hospital staff need to be hired in Ontario just to deal with staff turnover, hospital job vacancies, as well as the impact of the pandemic and the increased needs of a growing and aging population, according to the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions/CUPE.

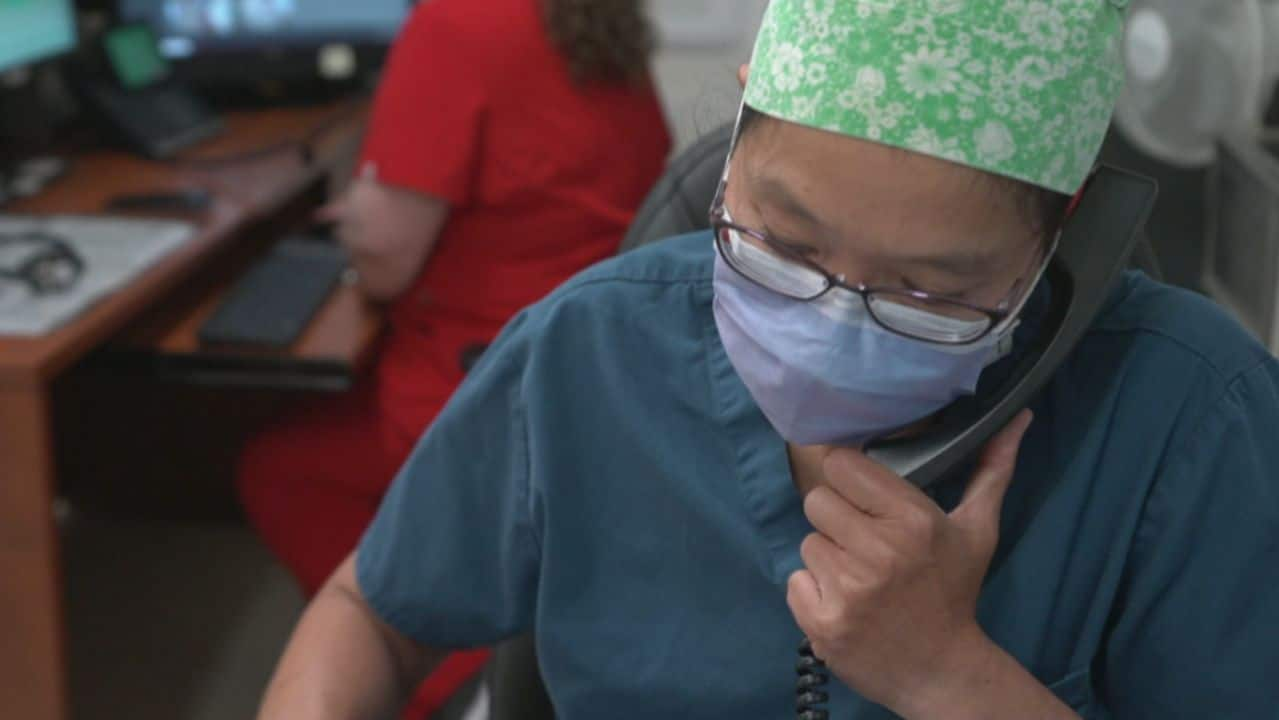

Widespread staff shortages in health care have forced Kingston Health Sciences Centre to shuffle patients between departments, occasionally close a section of the emergency department and treat people in hallways. CBC News’ chief correspondent Adrienne Arsenault witnesses the toll it has taken on employees and patients at the Ontario hospital.

In the meantime, the average emergency department wait time in the province is now at 20.7 hours for patients admitted to hospital.

When The National visited, Missy Calbury, 27, had already spent about 20 hours in a hallway in Section C and was waiting for surgery on her broken ankle. She said she didn’t realize how busy the hospital would be, until she came in and saw it for herself.

“I can’t really sleep, people going by, always in people’s way…. I’d prefer to be in a room, that’s for sure,” she told CBC News. “They definitely need more people.”

Hospitals of all sizes affected by staffing challenges

Kingston Health Sciences Centre is southeastern Ontario’s largest acute-care academic hospital, consisting of two hospitals (including Kingston General), a cancer centre and two research institutes.

Dr. David Messenger, the head of KHSC’s emergency medicine department, notes that despite the hospital’s size, it is by no means immune to staffing challenges facing hospitals across the province and Canada.

“One nurse makes a difference to our ability to operate sometimes,” Messenger said.

Rural hospitals, where staffing margins are often thinner, can be hit even harder by these shortages.

In Chesley, Ont., a small community in Bruce County, the local hospital has been forced to indefinitely close its three-room emergency department overnight, from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m., due to nursing staff shortages. At times, the emergency department is also closed during the day, too.

When the hospital closes overnight, any patients already inside who need emergency care will be seen. But as emergency and family physician Dr. Jacquie Wong told The National, as of 5 p.m., unfortunately, “anybody who comes to the emerg for care will not get it.”

The hospital provides a list of the closest emergency departments to Chesley for residents. The nearest one is in Hanover, 19 kilometres away.

“If it’s urgent, then we call an ambulance for them,” Wong said.

But she says the need for access to 24-hour emergency care is particularly important in a small community like this one, as it’s impossible for residents to plan for emergencies.

“We’re a big farming community, so there’s a lot of machinery involved, so you can have big accidents. Plus, you know … heart attacks or strokes or respiratory problems,” she said. “If you can’t breathe and you have to travel another half an hour, that’s terrible.”

Even though local nurses have taken on many extra shifts since the start of the pandemic, over time, “that takes its toll,” Wong said, and then they “just don’t have the capacity to be able to fill in those people.”

Amidst the pressures, Wong says, “we care, we want to provide care and we’re doing our best.”

The extreme staffing pressure on Canadian hospitals has forced some to temporarily close their emergency rooms. The National spent a day with staff at the Chelsey, Ont., hospital up until the moment they had to close the ER overnight because of staff shortages.

‘We’ve known this was coming’

Messenger says there are backlogs for patients throughout the health-care system that all culminate at the hospital emergency room.

“There’s literally nowhere to bring (patients) to because all the beds upstairs are full, and many of the beds upstairs are full because people need to go somewhere else for care in the community that doesn’t have an available space. So everybody waits, and there’s this progressive sort of series of roadblocks to moving effectively and efficiently through the system.”

The current situation, he says, has been a long time in the making.

“We’ve known this was coming … emergency doctors and nurses and organizations across Canada have warned that this was coming,” he said.

“The system hasn’t been given the resources it needs over a long period of time”

Messenger points to the fact that patients are getting older, meaning they have more complex medical needs, and people are getting sicker. Many might be without a family doctor. And, he notes, the mix of what they are seeing in the emergency department is changing — including mental health needs, and a rise in patients with substance-use disorders.

“We’ve really become the door to health care for so many people who can’t access it in any other way,” Messenger said.

A whole system under stress

Dr. David Pichora, president and CEO of Kingston Health Sciences Centre, says that the coming together of a number of factors — including staffing shortages, unmet care needs in the community and deferred care from the pandemic — mean that the whole system is under stress.

“Our ICU has been chock full for months and months and months,” he said.

ICU (intensive care unit) program manager Julia Fournier says her stretched staff often have to look for opportunities to try and “double” patients, which is a one nurse to two-patient ratio. At times, they “triple” them, which, she says, is unheard of in critical care, where the ratio would typically be one patient to one nurse.

On the day The National visited the unit, it had about half the staff they needed.

“I know the nurses provide excellent care, but it stretches them,” Fournier said. She is worried about seeing her team struggle “because of the moral injury and the moral strain. They’re tired. They’ve been through a lot with the pandemic.”

In addition to the occasional and temporary closures of a section of the emergency department, KHSC has also had to cap the number of patients they see at the Urgent Care Centre at their nearby Hotel Dieu Hospital to make sure there are enough doctors and nurses available to keep their emergency department running.

Pichora notes that their Urgent Care Centre is popular because people can show up without an appointment, see a doctor, or a nurse; and if blood tests, or an X-ray or CT scan is needed, it’s done right then and there. Many who come to their Urgent Care Centre do have a family doctor in the community, but can’t get an appointment in a timely fashion or need tests sooner than they can get them in the community, he explained.

The Urgent Care Centre is “a bit of a victim of its own success,” Pichora said, in that it is quite busy because it’s effective and convenient for patients. He cited it as a model to consider expanding further when governments are looking at how to redesign care in community health teams in the province.

‘We will care for you’

Organizations like the OMA and CMA are calling for systemic solutions to take the strain off of hospitals.

These include an increase in the number of health-care workers through such strategies as licensing more foreign-trained physicians and the creation of a national physician licence.

They also want improved access to primary care, centres for patients with less complicated surgeries, a better system of long-term care and home care for seniors, more hospice and palliative care services, more resources for mental health needs and substance abuse issues, and further work on digitizing health data and facilitating more virtual care.

Messenger said while they have worked to find efficiencies within the hospital, at this point the problems are so big that they really need broader system-level solutions and “legislative change that would allow an enhanced scope of practice for different types of care providers.”

“We’re emergency doctors, right? We’re action-oriented people and we like solutions quickly, and we like to move on to the next thing and solve problems,” he said.

Still, Messenger wants to reassure people that despite the challenges, they will be there for those who need care.

“People need to be aware that it’s not the same system it was 10 years ago…. There are going to be waits for less-urgent problems. But we will get to you. We will care for you.”

[ad_2]

Source link