[ad_1]

Over the last four months, you’ve sent us over 300 climate questions as part of the Great Lakes Climate Change Project.

We’ve researched the most commonly asked questions and given you answers about extreme weather, our water supply, and how you can both take action and stay optimistic in the face of the climate crisis.

Before we jump in, some general takeaways from your questions.

Most readers did want to hear about the many ways climate change impacts our lives, but also wanted a focus on solutions. A lot of questions were concerned less with what’s new and more on breaking down the long-term processes that have brought us to this point. That’s what we’ll be focusing on here.

In the face of danger, in the face of trouble, we all need to not just dig our head into the sand.– Xuebin Zhang, senior research scientist, Environment and Climate Change Canada

Some of you asked why we focused on the Great Lakes, and pointed out (correctly) that there is no such thing as a “local” climate issue. While true, the purpose of the project has been to highlight that these abstract, global concepts can be seen and felt right in Canadians’ backyards.

Through our form, we also received some climate denials. That’s not the focus of this story, but here are explanations on how volcanoes, solar cycles and other natural fluctuations affect the climate. Here’s an explainer on the Little Ice Age a few centuries ago, and one that summarizes (some of) the evidence that current climate change can only be caused by humans.

Ready to jump in? Let’s go.

This is the last article from the Great Lakes Climate Change Project. The project was a joint initiative between CBC’s Ontario stations to explore climate change from a provincial lens. You can leave your thoughts on the initiative at the end of this story, and read some of the highlights here:

Where and when can we expect to see more extreme events like storms, floods, wildfires, tornadoes and hurricanes?

Everywhere, and we’re already seeing a rise. Beyond that, this is a tricky question to answer.

This is largely because these phenomena are so unpredictable, said Xuebin Zhang, a senior research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada. As a lead author on the extreme weather chapter of the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, he and his team analyzed thousands of scientific papers.

It is often reported Canada is warming at twice the global average, but with little discussion of what that means. According to Zhang, even if the world manages to limit warming to 1.5 C, Canada will see a rise closer to 3 degrees — which has serious implications for our weather.

Generally speaking, we can expect more floods and heat waves across Ontario. Heavy rain events will become more common and more intense. Around the Great Lakes, more rapid and intense water level fluctuations could threaten homes and wildlife, and some winter storms could get more extreme.

Across Canada, the predicted impacts vary wildly between and within provinces, from stronger hurricanes in the Atlantic, to frequent droughts in the Prairies, to more wildfires in B.C. Research on changes to the number of tornadoes and extreme wind events is ongoing, Zhang said.

How do we know all of this? Painstaking research and climate modelling, Zhang explained.

We can’t know when these events will hit, but we know that they already have and will continue. While it’s difficult to attribute any single event to climate change even in retrospect, it’s not impossible.

World Weather Attribution (WWA) is one group working to address this problem by linking extreme events to climate change in near-real time — a huge improvement over the typical years-long process to publish a scientific study.

For instance, after 2021’s deadly record-breaking heatwave that killed hundreds in B.C., WWA’s small team of climate scientists took just weeks to put out their report, which showed the heat would have been near impossible if it weren’t for climate change.

Canada is known for its lakes and freshwater — will they be affected by climate change?

Perhaps fittingly, the most common question asked during the Great Lakes Climate Change Project was about how our freshwater sources will respond to climate change. The answer? Not well.

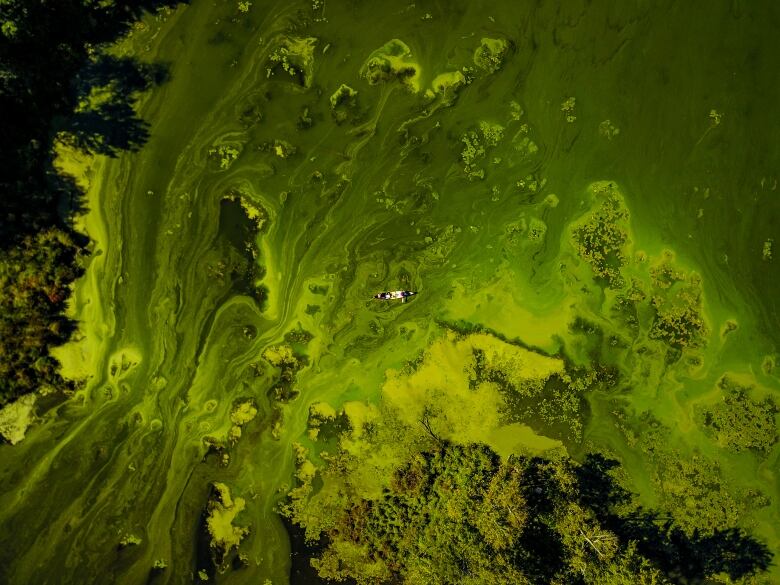

Already one of the major threats to our freshwater across the country is toxic algal blooms. They’ll only get worse with climate change, said Mike McKay, director of the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research (GLIER) at the University of Windsor.

We essentially have a bioreactor that will promote the success of these blooms.– Mike McKay, director of the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research

The main driver of algal blooms is agricultural practices, McKay said. Excess fertilizer and the removal of native, nutrient-holding plants around fields mean more nutrient run-off into waterways.

Climate change is amplifying this effect, since bloom-causing algae tend to do better in warmer waters — conditions that are only becoming more common, McKay warned.

Plus, with more intense precipitation events expected around the Great Lakes — and across Canada — even more nutrients will be leached from the watershed into lakes.

WATCH | Check out this time lapse of an algal bloom on Lake Erie in 2011:

“So we have a system that that is primed with high concentrations of usually agricultural nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus. We have a system with a prolonged period of stability and warmth.” said McKay. “[So] now we essentially have a bioreactor that will promote the success of these blooms.”

Even waters that have traditionally been resilient against blooms, typically cold areas with little agriculture, have been seeing more of them.

In Lake Superior, for instance, blooms have become more frequent due to warming coastal areas and two record-breaking rain events over the last decade that washed naturally occurring nutrients from the soil into the lake. Each of those rain events would historically have been expected to occur only every 500 to 1,000 years, McKay said.

In and around the Great Lakes, most blooms are caused by cyanobacteria, which produce toxins that can harm people and their pets, McKay said. Cyanobacteria are commonly called blue-green algae, despite not actually being algae.

Fortunately, Canada’s water-treatment protocols should be robust enough to withstand these events — though there have been incidents around the Great Lakes before, McKay added.

Still, blooms cause other issues. They can harm animals and pets that eat washed-up algae, disrupt aquatic ecosystems by causing the oxygen in the water to be lost, and affect water-based industries due to unpleasant sights and smells.

This isn’t limited to the Great Lakes. Algal blooms are becoming more common in places like Lake Winnipeg, in large reservoirs across the Prairies, and on Canada’s east and west coasts. McKay pointed to the dreaded red tide, driven by toxic algae that poison shellfish stocks, as one example.

To minimize the risk, we need to reduce nutrient run-off, McKay said. That requires no fertilizer use on lawns, as little as possible applied for agriculture, and a resurgence of native plants around fields and waterways.

There are other threats to our water supply as well. One is our groundwater reservoirs, which supply up to a third of Canadians — and 80 per cent of rural communities — with their drinking water.

Reduced snowpack means these underground aquifers, many of which are already being rapidly depleted, get replenished less each year. This isn’t a minor effect — climate change-induced drought and flooding are changing these groundwater reservoirs so much that satellites are able to detect changes to Earth’s gravity.

How can I avoid feeling hopeless? What can I do — if anything — that actually matters?

Some variation of these questions came up a lot.

Staying positive is a struggle for many people, especially younger generations, even though we know hope is crucial for climate action.

“In the face of danger, in the face of trouble, we all need to not just dig our head into the sand,” Zhang said. “The best way to deal with this is to be more optimistic. Because if you lose the hope, it will be even harder to cope.”

Sophia Mathur is a 16-year-old climate activist from Sudbury, Ont. She first started lobbying on Parliament Hill when she was seven, she attended COP26 and COP27, and was part of a lawsuit backed by Ecojustice concerning the Ontario government’s climate policy. The group said earlier this month it would be appealing the recent decision to dismiss it.

Even Sophia is not immune to the negativity.

“I’ve always seen myself as an optimist. I don’t like to admit it, but there’s obviously times where I feel like we’re not getting anywhere … but I think that working together with people, especially in a group, it’s definitely a way of supporting each other.”

Research backs that up — having a community and the opportunity for climate discussion are essential.

“I try to balance my activism with my social life and with, you know, doing things I love,” Sophia added. “I live near a forest, so I feel like going out of the forest and going out for hikes is kind of a way to realize what I’m fighting for.”

There’s strong evidence one of the best ways to avoid “climate nihilism” is to connect with nature — get out into a green space, appreciate why action matters. Getting to natural areas isn’t easy for everyone, but it’s effective.

McKay agrees that recognizing your relationship with nature is essential.

“[The Great Lakes] provide drinking water for 30 million people, provide recreation opportunities for, again, millions of people. It’s a resource worth protecting,” he said. “When you can bring it down to that level, look at the resource, relate to it on a personal level — people do the right thing.”

It’s also important to remember the success stories, experts said. From eliminating toxic pesticides to repairing the ozone layer, both collective and individual action have worked before.

“[The solution] is not to say that we are going to just wait and die ourselves,” Zhang said. “It’s not going to be easy, but we should be fine if we all work together to deal with it.”

One statistic that a few people cited in response to this project is that Canada “only” produces around 1.5 per cent of the world’s emissions. This was always paired with a claim that it means what Canadians do doesn’t matter.

While the percentage is accurate, it ignores the fact Canada makes up under 0.5 per cent of the world’s population — meaning we are producing more than three times our share of emissions per person. And that’s if we ignore reduction goals. It also leaves out the extent to which Canadians outsource their emissions to other countries.

There was also a feeling from our readers that individual choices don’t matter. In Canada, over 40 per cent of emissions come from households. According to an analysis from PBS, 20 per cent of emissions in the U.S. are directly from households — but that rockets to 80 per cent when you account for indirect emissions.

There is no denying climate change is inequitable. The richest among us are the biggest emitters, while the most vulnerable in our country bear the brunt of the effects.

Still, it’s important to remember that from a global perspective, the vast majority of Canadians are emitting disproportionate amounts while staying relatively insulated from the repercussions — at least as much as any inhabitant of our planet can be.

That being said, here’s a list of data-backed actions from the experts in this story and other sources that, if widely adopted, would actually make a difference:

If you want to dive deeper into the world of climate optimism, check out the latest episode of CBC’s Planet Wonder. For more examples of evidence-based actions, take a look at these pages from the David Suzuki Foundation and Environmental Defence.

For CBC’s Great Lakes Climate Change Project, the Ontario stations brought on a scientist to explain a few of the surprising climate change impacts and solutions that exist right at home, with deep dives into some of the science behind the stories. You can leave your thoughts on the project below.

[ad_2]

Source link